E. M. Forster, writer:

I see beyond my own happiness and intimacy occasional glimpses of the happiness of 1000s of others whose names I shall never hear, and I know that there is a great unrecorded history.

Susan Buck-Morss, critic/scholar:

As a graduate student in Washington, D.C., in the 1970s, I was hired to do research for a professor who could not travel there himself. I do not remember who he was or what he asked me to look for. But I recall the magical feeling of evoking the dead when, sitting in my chair at the Library of Congress, I summoned up a certain series of cartons to my work-site. They were brown boxes, ordinary moving boxes, on which was printed by hand “Captured German Documents.” They contained masses of papers, only partly sorted. In them, I tripped by accident over a birthday card sent to Hitler by his mother. It was the kitchy, commercial kind. Hitler’s mother had signed the card under its sweet-worded birthday wish. Hitler had saved it. The card survived the fiery bombings of Berlin and was discovered by a U.S. solder, who placed it in a brown carton along with the other papers. It moved across the ocean…. It was received with care by the authorities. It was put into deep storage at the national Library of Congress. Thirty years later, I was holding it in my hand.

Holland Cotter, critic:

The archive … is less a thing than a concept, an immersive environment: the sum total of documentary images circulating in the culture, on the street, in the media, and finally in what is called the collective memory, the ‘Where were you when you heard about the World Trade Center?’ factor.

Questions to ponder:

Think about it. Can you imagine a wedding without a camera present? A vacation? Your childhood? Are there any camera-free zones left?

Since its inception, photography has been instrumental in creating a warehouse of memory, cultural and personal. By the mid-1950s, an estimated two billion photographs were being made in the U.S. every year. Twenty years later, an estimated one billion Polaroids were made annually – not counting negatives and slides.

And now? Something like 50 million photographs are uploaded to Instagram daily.

The traditional purpose of the archive is both to preserve and to erase. As a society, we enshrine certain “memories” while burying others. As individuals, we did much the same: preserving memories first through the act of photographing and then selecting particular ones for the family album.

And now?

Reading / Looking:

- Okwui Enwezor: Archive Fever: Photography Between History and the Monument (excerpt)

- Hal Foster: The Archival Impulse

- Alain de Botton: Christian Marclay:The Clock And a video excerpt from The Clock

- Penelope Umbrico: Suns (from Sunsets) from Flickr [click through to the Flickr link at the end of the post]

Additional materials:

- Walter Benjamin: A Short History of Photography

- Holland Cotter: The Collected Ingredients of a Beijing Life

- The Way We Live: Drowning in Stuff

- Curating a Gallery of Garbage

- A Master of Accumulation

Artists to consider: Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter (Atlas), Christian Boltanksi, Tacita Dean, Sherrie Levine, Thomas Hirschhorn, Karen Kilimnik, Jiang Jian, Zoe Leonard, The Atlas Group

PPT: The Archive

I discussed this very issue in our first writing assignment and as Enwezor argues in his essay this need to “archive or preserve” dates back to the very inception of photography Walter Benjamin’s writings.

I must say that I was really impressed by Marclay’s “the clock”.

I thought this was absolute genius and it does in fact reveal so much about the culture in which we live and our increasingly intense relationship to time. We are obsessed with youth, with as Franklin said “time is money” in a capitalistic society and with the idea or boarding on fixation with our own mortality. In this culture we SPEND time, we don’t experience it.

As I had mentioned in my first essay my family (for no particular conscious reason) after about the age of nine (for me) totally stopped using cameras. Less than three rolls of family photographs exist between then and now. We don’t use cameras , I don’t know why, I don’t think anyone does but it’s abnormal. As for my personal life I of course use cameras but I don’t like to document my life and I don’t. For me cameras are a tool used specifically for the reason of creating art and that’s that. Ok, I do snap a shutter on an occasional candid moment but so few and far between.

Tied in with conceptual territory covered by “The Clock” we are also a crude that seems to suffer from the mass delusion that by archiving and by sharing the trivial details of our lives we are somehow “slowing time” or reaching for a sort of pseudo immortality. We refuse to accept the notion that we are small I significant and transient. I personally do not photograph my life because I do not wish to have memory perverted by trace claims to “objective truth”. I’d rather let my memories fade into what they become and I hope they will be beautiful.

In a way the story of the Chinese family and that piece (which the whole the thing was very strange by the way) is another way in which we use things, pictures, possessions to stand in for what is really lost and faded into the ether. A sort of simulacrum of sorts (to reference an earlier reading).

Also, the article drowning in stuff reminded me of a disconcerting experience I had with a student last year. Apparently this student had heard I was “good” (whatever that means) and wanted to see my portfolio. I handed them an iPad upon which they went blazing through my portfolio spending about 3 seconds on each piece (I’d myself forgotten the special things about these photographs) and they handed it back to me with a very sincere “that’s amazing!” (Thinking and believing they’d seen and understood it) If I was in a worse mood my response would have been “that’s the best compliment I’ve ever gotten from someone whose never seem my work” but I was in no mood to be a jerk. I went up stairs to gallery 1401 and saw a show about the over flowing landfills in India and albeit a loose association, the odd interaction I just had was totally contextualized. Our minds are over flowing with images, sounds, media at a point of critics mass. A total breaking point. It all made sense. The way we are living is spiritually dangerous.

I couldn’t agree more, and I could add a lot but basically it would just be more stuff. Reticence has its place, but we seem, collectively, to have forgotten.

What I gather from the texts from Okwui Enwezor and Hal Foster and the Marclay video, is that since photography’s inception, there has been a growing fear or paranoia about remembering and being remembered. From this theory, stemmed the rise of consumerism in photography and companies like Kodak capitalized on our indulgences of validation and fears of losing something. (Sounds a lot like insurance companies). There has been an unprecedented rise in just how many photos are being taken, shared, and uploaded to the web compared to how many photos were taken before digital. This convenience factor of putting a camera in so many more hands today is evidence of people’s desire to let the world know that they are here and they are important. What was once considered a scientific and purely archival process has, or perhaps, is still in the process of, reaching it’s potential. It is now a commodity to the masses and people would rather look at a photo of someone else’s lunch than at something with a significant purpose in the world. The photograph’s purpose in society has been transformed over time, its uses are vast and is implemented in societies cultures throughout the world. Because photography is so much more accessible than ever before, digital has in a way, weakened the way we think about photography and also how we take a photograph.

People cherish their memories and while some may want to look back on them in a tangible manner, the more modernized system of archiving on the Internet totally shifts the way in which we reminisce. Tangibility, is something, I hope most photographers hold dear. Yes, you cannot deny the great convenience and benefits of online storage, but you lose that quality of touching something real if that photo never comes to print. It’s simply a memory made up of 0’s and 1’s that are displayed on a screen and as many agree, digital is just colder. Why else would the instant print systems like Polaroid and now Fujifilm never really go away entirely from society? People still want something to hold.

There are two meanings of “archive” floating around in these readings: one any “official,” third-party archive (the official record of your existence from birth certificate on, the data file Amazon has on you, the record of a library’s holdings, criminal records, etc.) and the other the kind of informal, unplanned, largely first-person collection of photographs, papers, letters, Facebook posts that individuals maintain about their own lives. While both of these entities threaten to swamp us, they function differently: the former to classify and hence control; the latter to document? serve as a surrogate memory system? prove we were here?

You’re right in thinking that, for many people, the digital / internet technologies that so dominate our lives can feel limiting in their limitlessness. The tension here seems to me to relate to the whole mind-body split: the internet places us firmly in a disembodied, mind-based space where physical presence is underplayed. But we are physical beings who live — and die — in the physical world,

Machines are made to make human life easier and “better”. Machines made to document and to record human life make memory easier to access. They might even encourage humans to remember less in their minds. Images are collected constantly through the eyes and are translated to the brain. As time goes forward human memory dissipates and many times decays. The camera and the photograph help to keep the images alive and archivable. The archive as an object is some what magical. Photographs from different times are like moments or memories from another time. The difference is that everyone can experience a photograph but not everyone can share a memory. I think that this is one of the most important aspects of the photograph archive. One must ask how many photographs make an archive though? The excessive amount of photographs that we have today makes a complete archive seem impossible in a physical sense.

Okwui Enwezor speaks about how the photograph quickly becomes an archival object in the world where it captures the culture, fashion, and government. The media takes from these archives and produces opinions and narratives. The archive as a tool is not foreign to the world either. The internet has become the largest archive know to the world. Images from camera and other documentative tools exists on the internet ready for people to make use of. Again its almost unimaginable to know or to experience how many photographs are in existence. This is wonderful in a sense but terrifying at the same time. A photograph of your face, of your family, of your everyday routine might be in that archive ready to be sourced.

“The difference is that everyone can experience a photograph but not everyone can share a memory. I think that this is one of the most important aspects of the photograph archive.” Nice point and a good description as any of the benign purpose of the archive: it offers us a door into another experience–either individual or collective (as exemplified in the difference between leafing through someone’s picture album and researching a library’s holdings on an historical event).

“One must ask how many photographs make an archive though? The excessive amount of photographs that we have today makes a complete archive seem impossible in a physical sense.” It does seem to have swamped us, doesn’t it? It fascinates me that, even so, some photographs manage to break through the noise and capture our collective attention.

“This is wonderful in a sense but terrifying at the same time.” This is the textbook definition of “the sublime.” A presence so grand and so much more powerful than we are that it fascinates, enchants, and terrifies. I suppose we are witnessing something like the digital sublime.

a few things right off the bat, the suns are awesome. It’s officially my screensaver, it reminds me of what I would see right before I die form someone reason or something that would be in reqium for a dream, in-between scenes. The Clock piece, made me SO anxious and I realize that’s intentional and almost inevitable because we are always battling time. people wanna make it slow down to avoid death but we also wanna speed it up so we can get past the mundane activities and onto the “fun” things in life etc. My Opa constantly is saying, “god gave us 24 hours in a day, and it’s up to us what we do with them.” He says it so frequently that I often find myself in the middle of an anxiety attack when I realize how many hours I wasted watching Dexter, or like the narrator says in the Clock video, how manny hours I ‘ve wasted on feeling regret, feeling unhappy, just letting time pass me time. Forgetting about time is almost impossible for me personally. Im hyper conscious of it, and I often think about the archival aspect of photography in that it allows me, and everyone who uses photography or really any kind of art, to make a mark on the world somehow, no matter how minuscule that mark may be. I’m really interested in this notion that archiving things allows us to choose what we remember or value as an important memory. As someone with post traumatic stress disorder and someone who struggles with repressed memories, I relate to this idea completely differently than someone who is just an artist ( and I don’t “just an artist” as something bad). My brain made these decisions with out my conscious awareness as a child. It chose what to forget and what to remember based on what I mentally was capable of comprehending and emotionally able to deal with at a young age. As a photographer who is consciously aware of the environment they are documenting, you DO have control over what is remembered and what is forgotten. It’s both scary and beautiful because, especially now, when so much of life is out of our immediate control, at the very least, we can decide for the future what other people will take in from this time. What is scary about that, is the information recorded it a bit subjective to that particular creator/recorder and that could leave out important information or images for future generations.

However, like Adolf Hitlers birthday card, when reflecting on the past, it is interesting to see and analyze what people found to be important to them as individual. What kinds of things marked existence or purpose for them.

What people choose save and discard.

How people process the world and environment they are living in or visiting.

Pictures give us visual land marks on time and the effect time has on humans. I firmly believe though, above all, photography makes us feel like our time alive is real. We existed in some form or another, and we can prove it to people after our time.

At the heart of the problem of the archive is exactly who is making the choices and to what end. An archive, strictly understood, is an official repository — something maintained by the state or an institution (library, university, corporation) — as distinct from a personal record (that would be more like a scrapbook, I suppose).

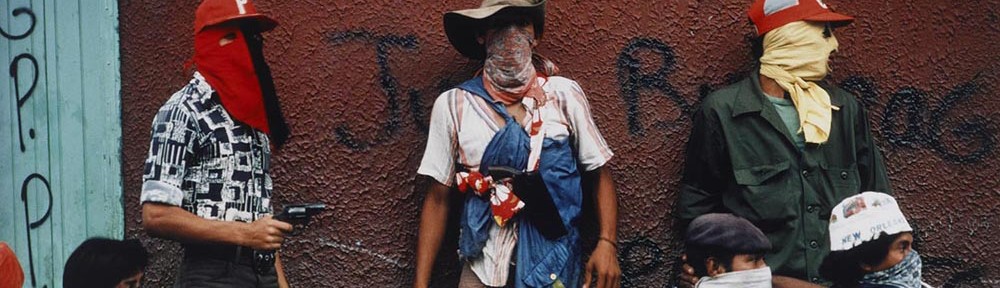

And the question then becomes political. What is “worthy” of archiving? Who is “worth” remembering? What is discarded? Who is ignored? What is not even in the running (doesn’t even rise to the level of consideration)? A few decades ago, historians began to wonder about a whole slew of questions about the past — what saw the sewage system like back in the day? what did “the simple folk” wear? where did they sleep? The focus shifted from the top-of-the-heap folks (kings, popes, famous artists) to include the rest of us.

But the work in discovering what the lives of those at the bottom of the social ladder was difficult: BECAUSE THERE WAS NOT MUCH OF AN ARCHIVE.

On an entirely different point, I agree with you about photography serving to prove somehow that we were here. Which is, arguably, what all art does. Among other things, of course, but fundamentally it is a testament to the artist’s presence on the planet.