Umberto Eco:

The postmodern reply to the modern consists of recognizing that the past, since it cannot really be destroyed, because its destruction leads to silence, must be revisited: but with irony, not innocently. I think of the postmodern attitude as that of a man who loves a very cultivated woman and knows he cannot say to her, “I love you madly,” because he knows that she knows (and that she knows that he knows) that these words have already been written by Barbara Cartland. Still, there is a solution. He can say, “As Barbara Cartland would put it, I love you madly.”

Reading / Looking

- Roland Barthes: The Death of the Author

- Jean Baudrillard: Simulacra and Simulations (excerpt)

- Joachim Schmid: Other People’s Photographs

- Fernando Pereira Gomes: Procedural Generation

What the … ? The provocative title notwithstanding, The Death of the Author does not mean that there was not a person who thought, felt, planned and wrote. What Barthes is questioning is what we mean by authorship itself. How is meaning created in a work of art? Is it the product of a single intelligence (the author, the artist)? Something he/she imposes onto the piece? Or is it rather created from a complex web, drawn from our particular culture’s artistic conventions, previous artworks, and the whole archive of cultural meanings? And once launched into the world, is it then “co-created” by those of us who receive it? That is, what is the role of the viewer/reader in creating the meaning of a work of art?

And Baudrillard! In this excerpt, he is assuming a proliferation of images in advanced capitalism, with the expansion of commodities and technologies like television, film, photography (and now the computer and its spawn). He traces the movement from representation (of something real) to simulation (with no secure reference to reality). This shift severs the connection between the sign and the reality to which it has been traditionally thought to refer. For Baudrillard, we are now in the realm of hyperreality, situations (like Disneyland) where the sign or image now usurps “reality.” (Again, a gross oversimplification!) Do you find this line of thinking persuasive? Any examples (other than those Baudrillard has offered up)? Or does this notion that we’re living in what amounts to a house of mirrors seem to you (as it does to many critics) like a crock? Again, provide concrete examples.

Questions to ponder:

Many of the artists labeled “postmodern” pioneered “appropriation” in their work—an approach to art-making that raised many questions. How much prior knowledge is assumed for the appropriation to “work”? Can the newly constituted work stand on its own? Artists have responded to the work of their predecessors for centuries. How does, say, Richard Prince appropriating advertising imagery differ from Manet riffing on Goya, riffing on Titian and Giorgione? Does it? Could the difference we all seem to detect lie in the tone, the intent of the artists? In other words, are we talking about the difference between homage and irony? Do you see qualitative differences between the varying approaches of Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince, David Levinthal, and Cindy Sherman?

PPTs:

Ok, so this is an interesting discussion and I have a lot to say.

When we talk about the death if authorship yes, I see what Barthes means when it comes to the notion of appropriation and authorship, however, there is another related topic to address first.

Process based photography is something relatively new in its scope (of course people like MoHoly-Nagy were doing this work with photograms early in the century) but it’s risen recently. Images such as my own Chemical photographs, Scott Mcmhon’s firefly work and the work of many other artists are in a category that all of its own in certain regards. The photographer is rather unimportant in such work as take my chemical work for example, all I am doing is “illustrating” and making tangible a phenomenon that is in no way contingent on my existence. I simply made an observation about said phenomenon and set out to make “artistic illustrations of a scientific phenomenon”. It is only within a narrow and silly paradigm of the art world and culture that today I sign my name on the back of these prints and I’m totally sure why. The same can be said of McMahon.

As for appropriation this is a dicy topic. Artists like Paul Cava and Jeff Cowen heavily embrace this notion in the service of creating something totally new; full of soul and spirit that is alive and is bursting at the seems with energy. The fact that many images were not captured with a camera by this artist in particular is of no consequence and is totally valid. However, I can think of many instances where people are simply not skillful technicians and also seem to lack the ability to appropriate images in a way as to make them in any way compelling or interesting. I could name names but some of the worst offenders that come to mind would get me in trouble so I’ll pass… In short, anything goes if it comes from a place of truth and is compelling and it doesn’t fly if you’re playing the art card”.

As for simulation or hyper reality yes this is certainly an emerging trend. Take the work of people like Crewdson for example or Phillip Lorca Di-Corcia whose use of lighting, scale of sets and aesthetic are certainly rooted in the “real life” but yet they are transformed other worldly and yes, “hyper real”.

As for Simulacrum, take the hand painted landscapes of David Lebe. Working with a photograph he creates worlds and universes that are totally imagined, channeled and have no point of reference in any type of objective reality. The same goes for the work of Ed Mapplethorpe (not Robert, Ed). His gestural camera less chemigrams resemble the work of the new work school of painters; more in the vein of Jackson Pollock or Motherwell than any “photographer” I can think of. These artists create words all their own with no reference points.

As for the brief article on the photo realistic video game, I have personally been experimenting with combining computer generated imagery with camera captured imagery. Where does it end and why make the distinctions? Does it work? That’s the only thing that maters to me.

I take your point about process-based photography but would like some clarification about what you mean when you say that all you’re doing making tangible a phenomenon that is in no way contingent on your existence. I grant you that the phenomenon is not contingent on your existence (although your status as an observer of said phenomenon could be said, per Heisenberg, to change the phenomenon observed — but leave that). But you seem to elide over the “making tangible” part of the equation, and in so doing, seem to be downplaying your role. You do, in fact, have a great deal of agency in this scenario: not perhaps in the same way as Crewdson, say, but you do make the work, choose the process, select the moment, the particular chemicals, work the print. Hence, the art world’s interest in your name. It’s your idea. It’s your execution.

Regarding appropriation: when you talk about people being insufficiently skillful and / or unable to make compelling images, I’d respond: sure. Some people are better artists than others. But I suspect that you’re saying something a bit different: that is, that you are making distinctions between different types of appropriation. Or perhaps the scale at which different artists practice it? My guess here is that you see a difference between artists who use appropriation as part of their toolbox and those for whom appropriation is the only tool.

For the purposes of my thinking here, the issue of “quality” is moot. I’m interested in the meaning of the phenomenon as it is currently being practiced and understood. That is, what does it mean about the state of the culture — its underlying values and philosophies — that appropriation has become so widely and so self-consciously practiced?

I would also agree that what matters is what works. Why make the distinctions? Because it’s in making the distinctions that one comes to glimpse something of the mind that made the work and hence the depths of the work itself.

It is difficult at times to be an original source of creativity and imagination without having “appropriation” come into consideration. We live in an age where it seems like limitless information spreads around the globe and gets regurgitated every few years by means of culture and politics. It is especially difficult to discuss post modernistic approaches that artists use, seeing as I feel that we are presently working through a phase of this era. Hence, my use of the term limitless, it is a vicious cycle of one thing being interpreted enough to pass as original content after another. I wonder if artists who are considered to have been the first to do something had been influenced solely by pure imaginative cognition. True, it is said that we are influenced by our surroundings, but history has shown us that influence can also derive from what is within. I was told once, in regards to creating new artwork that, “Everything has already happened, but it hasn’t happened to you.” I would like to believe that there is still a void in the realm of creation that will never be filled, only the truest and most unique survive, which as time has shown are rare, and often times, unnoticed until the artist is no longer living.

It also can be argued that this process of appropriation for post modern artists can be linked to the conception of the internet or perhaps even the Industrial Revolution. Yes, there are visible traces of appropriation and influence by artists predecessors prior to these events (Titian to Manet), but these were major events that altered the way in which people lived their lives, specifically in regards to speed. This ultimately has the affect to broaden the reach of viewers and influence at a rate that had not been seen before. So what had taken some 200-300 years to rediscover an appropriated piece, someone right now could be doing it in seconds and thus producing a significantly higher amount of appropriation from emerging artists. It is still very much a part of our culture, more so than ever before.

I think that people, artists in particular, often think about what deems their work as their own. In regards to Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince, David Levinthal, and Cindy Sherman, I think each one has something to say and that their approaches, perhaps debatable at times, are still valid as each say something different. To compare them as artists, and I can say that there certainly are qualitative differences that distinguish their individual approaches since each of them faced the same conflicts that rising artists struggle to surpass. To prove a point, using the camera as a tool to send a message such as each of these artists have done, is distinguished by their uses of appropriation. This is the path these artists decided to use and they are certainly not alone, this is to say, that we may all appropriate something in our work at times, but it is our responsibility not to abuse it.

Do you see a qualitative difference between Manet’s riffing on Titian and, say, Richard Prince riffing on the Marlboro Man? I think that the pomo argument of artists like Prince and Sherman is that the conditions under which we live now (an image-, media-saturated world) are fundamentally different from any previously experienced.

When David Levinthal brought his Hitler Moves East work into his Yale graduate seminar, his teacher asked why he didn’t photograph the world, and Levinthal replied that he was photographing the world. (Or so the story goes.)

Levinthal’s set-ups were clearly influenced by combat photographs, but the “influence” seems a little different than Titian’s on Rubens and Rembrandt, or even on Manet. In no small part, I think, because of Levinthal’s stance — the ironic distance he puts between himself / us and his subject. Even Manet, who did engage in a kind of distancing — distancing us from the illusion of painting by insisting on the flatness of the painting, distancing us from the illusion of the sensuous nude by depicting a coldly calculating courtesan — even he didn’t take it so far as to paint a toy.

I guess the question here is when does influence become appropriation? Or does it?

I personally had a really hard time understanding the Baudrillard excerpt. I think it’s just the way he writes, but what I gathered, and I’m sorry if i’m extremely off base, but I think he’s saying a few things. 1. The map is a representation of an empire that no longer exists and so it’s not real, it’s the hyper real. It’ s something that once existed but deteriorated along with the map that made a real space into a small image, which is also not the real.

2. I think he’s also saying, people are losing sight of what’s real, rapidly because truth and lies are becoming harder to distinguish as the world grows older.

3. If someone says something is real and their body shows signs of it, even if they made it up in their head ( example: hysterical pregnancies), is it actually real then? Or is the person a liar, lunatic, hypchondriac etc. Even so, what is real about those characteristics in a person. Can you prove someone is those things, or are they just manifistations of their imagination. Can imagination be a real thing?

4. Lastly, I feel towards the end he basically says, in a more polite way, Americans, can’t deal with the real world and so they would rather play pretend so much and so often that it becomes/ they accept it as their reality but it is a false reality.

What I don’t get, is the icon part. I don’t personally think the Iconoclasts destroyed images because the pictures made them realize God DIDN’T exist. I thought they destroyed them based on biblical principles that deterred the worshipping of idols and images. It was described as a sin in the Bible.

I don’t know, this might have been one of the hardest readings for me but I think that’s because it was all about whats real and what not real, and that starts to get very philosophical almost TOO philosophical because honestly what IS real?

Yes. it’s a challenging piece of writing.

Today, “reality” has been supplanted by simulacra. In my neighborhood, a townhouse development features “columns” at the front door of each house but the columns don’t hold anything up and they don’t even pretend to since they’re just slapped on and hover above the foot of the house. Those columns are simulacra (copies of something that was once “real” in the sense that it functioned) but now are in the realm of what Baudrillard calls the hyperreal.

What is more, those columns? They are (obviously) not “real” columns since they support nothing. So what are they? Why are they there? They signal a lifestyle (of wealth), a myth (of gentility).

In his discussion of the icon, he is suggesting a progression of the image from:

1. Something faithful to reality (a portrait, for example)

2. Something that perverts reality (the icon, maybe a caricature)

3. Something that pretends to reality but only masks its absence (Disneyland)

4. Pure simulacrum: the image has no relation to reality whatsoever (maybe something like Second Life? Or the “photographs” taken inside Grand Theft Auto? My columns?).

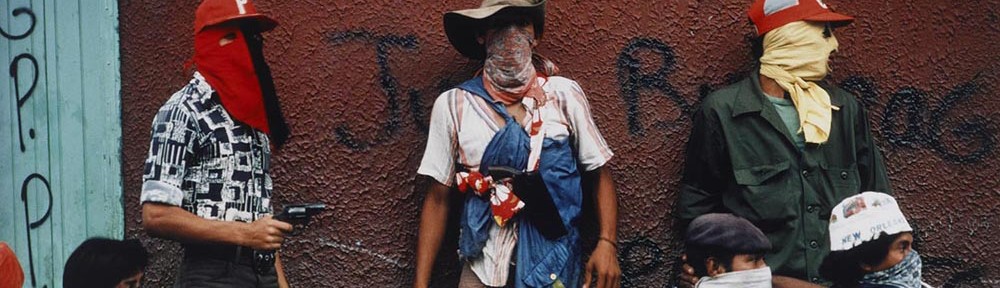

Baudrillard ascribes our hyperreal world to a number of things, but one of the major causes is media culture. Things like this:

http://www.nextnature.net/2007/03/simulacra-for-dummies/

Does the author of the text the reader is reading matter? One could say that the author is just made from the culture that they live in. Therefore the given author them self doesn’t matter but the culture in which they have lived should be taken into perspective. This ignores every nuance and genetic and chemical displacement from human being to human being. Thought process is not necessarily derived completely from the culture. A single culture can not contain the world and that is precisely what modern authors have access to. We ask how Tolkien thought and made decision because we want to understand the individual instead of the time he lived in. Personalities are much more attractive to some than cultures that have had a hand in shaping them. Each fantasy an author makes doesn’t have a home in the culture that he or she made it but in their very own minds. I understand the phrase “once the author dies” but does the author really die when the book is finished? Sequels and prequels and series from the same author keep the story alive but it also keeps in mind that the author can make a continuation whenever they please. When ever a different author continues a known story it can feel very much the same but somehow different.

I deeply care about the author when the book relates to my life. I don’t simply think that the book is wonderful, it relates to me, stop. I realize that the author has gone through or is knowledgeable of things that relate to my life. If the author of the book is not known that doesn’t stop people from understanding that someone wrote it out based upon their ideals.

There are many people involved in the creation of video games. Character direction, scenes, “extras”, and plot are all non-existent till the moment of creation. Once these entities are created and put in their respective plots in the program they begin to commingle with each other. Whether thats through being closer or set apart from each other it tells of the pre-determined relationship they are to have. The act of taking picture in the video game GTA5 is akin to walking into another God’s universe in the skin of one of its created beings. When you walk around the world someone has created the characters can see you and many times react to you. Is it any less real because they were created in a video game? If we liken our life to one big video game taking pictures in this universe isn’t that different than GTA5. Of course everyone is reluctant to say that this life is a video game or program. The fact of the matter is that for any photographer that is in favor of a creator of this world probably wouldn’t find it erie that they pictures that you can take in GTA5 give you a surreal feeling. It’s just another creators universe.

Your argument is essentially in defense of a traditional understanding of the individual author’s role as “creator.” What Barthes suggests is that the author’s intentions and biographical facts (the author’s politics, religion, etc) don’t really matter in the interpretation of the work. We tend to valorize the author and underplay the extent to which he/she is drawing on the stories and myths of the culture — retelling them, if you will. Tolkien, for example, drew heavily on Norse mythology, Catholicism, fairy tales, Celtic myths, etc., in constructing The Lord of the Rings. This is not to say that Tolkien didn’t put in the hard work of writing the books, but rather that we shouldn’t ascribe ALL THEIR MEANING to his particular genius. In fact, Tolkien himself said: “I think that many confuse ‘applicability’ with ‘allegory’; but one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other resides in the purposed domination of the author.”

It’s the domination of the author that Barthes is arguing against. And for the freedom of the reader.

As for photographs from video games, they seem to me like pure simulacra — having no relation to any reality whatsoever. A near-perfect illustration of Baudrillard’s idea of hyperreality.

Roland Barthes articulates, in so many words, that modern literature, once on the page and in the hands of the writer, is devoid of the author’s true voice. By this, he means that, “this destination cannot any longer be personal: the reader is without history, biography, psychology [of the writer].” This issue also arises in my art therapy classes. We call it projection. A client can project onto a page their innermost emotions and fears, and as therapists we can make educated guesses at what they are trying to sublimate. Just as psychoanalysis comes with its own dangers of projection from the analyst, interpreting literature can also be ‘dangerous.’ This reading has different puctum for each person that reads it. What I pull from is going to be different from what you pull from is going to be different that what the writer intended and there in lies the ‘danger.’

Barthes also plays with the idea of originality in content. As artists this is an important concept to consider. Now more than ever, over the course of my research for thesis, I am slowly coming to find that every picture has already been taken, every topic has already been chewed, but where I can alter the viewer’s experience is in my intent and visual approach. Even making that assertion edges on presumptuous because there is no way for me to know that someone out there isn’t shooting the exact topic with an identical approach. Consider any work of art about the nude body. This topic is made, attacked, and then remade with every attempt. The artist must consider every example that comes before them, and then must consider how they can set themselves apart from every example that comes after.

An interesting analogy — although I would like to suggest that we do actually share collective experience, memory, ideas, etc. (all that adds up to the idea of the “culture”). And we draw on that larger collective knowledge as well as our own internal experience. Indeed, it’s an interesting question to what extent our internal experience is shaped by that collective knowledge. For instance, how much does our language — the words we have to express things — shape what we can express?

As for originality, here’s a question for you: why do we value it so? Other places, other cultures, other times have not been quite so enamored of it. Rather the craftsman learned the master’s craft and set out to replicate it. Innovation slipped in, of course, but slowly and not necessarily intentionally — often because of interaction with other traditions. But the idea that it was the artist’s job always to make something new? Not so much.

Ecclesiastes 1:9 (written sometime between 460 and 130 BCE): “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again there is nothing new under the sun.”

Sorry for the very late response! This one slipped through my fingers.